Fast Fashion and the Impact on Labor

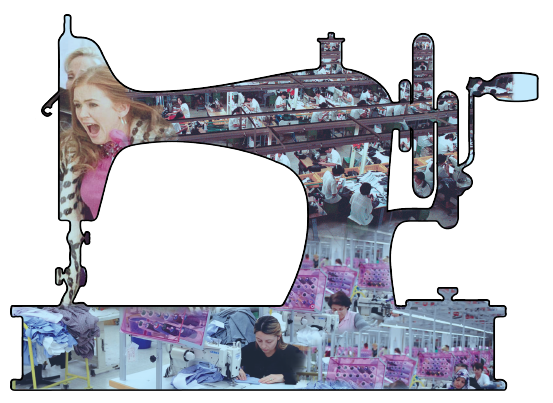

Graphic produced and owned by DPR Designer Erika Ortega

The downfall of Forever 21 marks more than just the end of quirky graphic t-shirts with taco references. It signifies a revolution in consumer preferences, a shift from the fast fashion industry to more ethical and sustainable clothing brands that are now taking over the market. Fast fashion’s reliance on sweatshops that violate labor codes, is turning customers away from mass produced fabrics.

Forever 21’s decline was ultimately due to the corporation’s inability to adjust to the changing customer preferences, leading to a significant drop in sales. Part of Forever 21’s errors lie in its failure to create a larger online presence for itself in an age when e-commerce accounts for more than half of retail sales growth.

However, the company’s mistake in expanding physical retail stores instead of online presence was not the only weakness; Forever 21 neglected to address its changing customer bracket and their preferences. The current target customers of Forever 21 are of Generation Z, typically described as people who are born after the mid-1990s. This generational cohort is characterized as caring deeply about work ethics and prioritizing environmental sustainability in their purchases.

The business model of fast fashion gravely contrasts the values that Forever 21’s new consumer base holds. In 2017, wage claims were filed with the state of California by factory workers who worked 11 hours a day with a wage of six dollars an hour. These factories were owned by Forever 21, TJ Maxx, and Ross Dress for Less.

Though one could argue that the United States has made efforts to curb labor code violations within its borders, sweatshops are even more prevalent in developing countries. The production of clothing worn by Americans has been gradually moving overseas since the 1970s. Today, less than three percent of the clothes sold in the United States are made within the country. Moving production overseas grants manufacturers the benefits of laxer worker protection laws and cheaper labor.

The economies of several developing countries often primarily rely on their textile industry. But despite this, workers laboring in the factories have little to no worker rights and are paid less than the minimum wage needed to survive in the region. In Bangladesh, the textile industry accounts for 80% of the economy’s exports, but the estimated 4,800 factories erected there by popular US and other international brands pay workers just 10,700 Taka (Tk) a month (approximately $125 dollars/month), which is far below the 16,000Tk a month required to stay above the poverty line.

Workers in Cambodian factories for popular athletic-wear brands such as Nike, Puma, and Asics reportedly had over 500 hospitalizations in the span of one year. Much of the health concerns in Cambodian factories regarded workers fainting due to interior temperatures as high as 98oF, which may be a result of the lack of temperature regulation laws in the country.

The inhumane treatment of workers through the aforementioned factors, along with others such as verbal and physical abuse often leads to deaths in the workplace. But despite these conditions, sweatshops for international companies are still popular amongst laborers in developing countries as they pay more than the wages offered by the country's ruling elite. This, in turn, grants the employers more power over the laborers; since labor is so readily available, workers cannot protest or take days off because employers can simply hire someone else.

The string of disasters in sweatshops from 2012 to 2013 brought concerns over labor conditions back to mainstream attention. The collapse of the Rana Plaza factory, that killed 1,134 workers, is one such case in point. While companies took some action towards improving conditions, the agreements were poorly implemented, and have not done much to ensure the wellbeing of workers.

Though the need to alleviate the physical and psychological stress on factory workers is evident and immediate, the question as to how still remains pertinent. US consumers have recently chosen to adopt some of this responsibility, evidenced by the recent rises in popularity of thrift shopping and ethically produced clothing brands, such as Reformation and Everlane. These brands have also made significant efforts towards reducing the environmental impact of fashion by reducing water usage and emissions in the production process. In fact, each clothing item from Reformation comes with a “care label that actually cares”, with instructions for the consumer to continue conserving water and reducing greenhouse gases after the garment is taken home.

Opting for thrift shopping and ethical brands decreases the demand for fast fashion, which, while being advantageous for environmental health, also decreases corporations’ demand for labor, leaving the sweatshop workers with even less to live off of. As the economy of many developing countries rely on clothing production, this has the potential to cause harm.

The wages paid by the sweatshops, though minimal, are three to seven times higher than the wages paid by other work opportunities in these developing countries. Despite harsh working conditions, the lack of better labor openings force sweatshop workers into believing that the slight benefits they receive outweigh the extreme opportunity cost of working elsewhere.

Though well intentioned, the act of shutting down these factories can have very negative consequences for the workers. When child labor was discovered in Walmart factories across Bangladesh, the United States passed legislation that prohibited the import of goods produced using child labor. As a result, the factories stopped hiring children, but instead of going to school, these children turned to worse jobs, or ended up as prostitutes.

So how exactly can this seemingly unsolvable problem of fast fashion labor be resolved? The CGS 2019 U.S. Consumer Sustainability Survey of 1,000 consumers showed that about 47% of United States consumers, most of which are comprised of younger generations, are willing to pay a markup for products that are sustainably and ethically produced. Since the minimum income needed for sweatshop workers to support life above the poverty line is low compared to the US dollar, even a slight increase in the prices of garments could have a significant impact on the workers’ livelihoods.

Global companies have also begun to seek certifications that earmarks their products as sustainable for easy identification by consumers. The Worldwide Responsible Accredited Production (WRAP) is one such certification. WRAP incorporates the general practices upheld by the International Labor Organization in their certification process and ensures that “human resources, health and safety, environmental practices, and legal compliance” are maintained throughout all aspects of production. Encouraging companies to go through the certification process and clearly mark their products as sustainable could also serve to foster better work conditions in textile factories.

The bankruptcy of Forever 21 may parallel the rising consensus against fast fashion production methods, but whether or not the bankruptcy will mark the end of unethical labor conditions lies in the hands of both the consumer and the corporations. Working to improve labor codes and working standards in the countries that rely on sweatshops may prove to be more effective in preserving the workers’ well being than opting for the sustainable brands while shopping for your next long sleeve turtleneck for the winter months.