“Even the Sky Above You and the Very Ground...Are Possible Threats”: Mitigating Aid Worker Attacks and Deaths

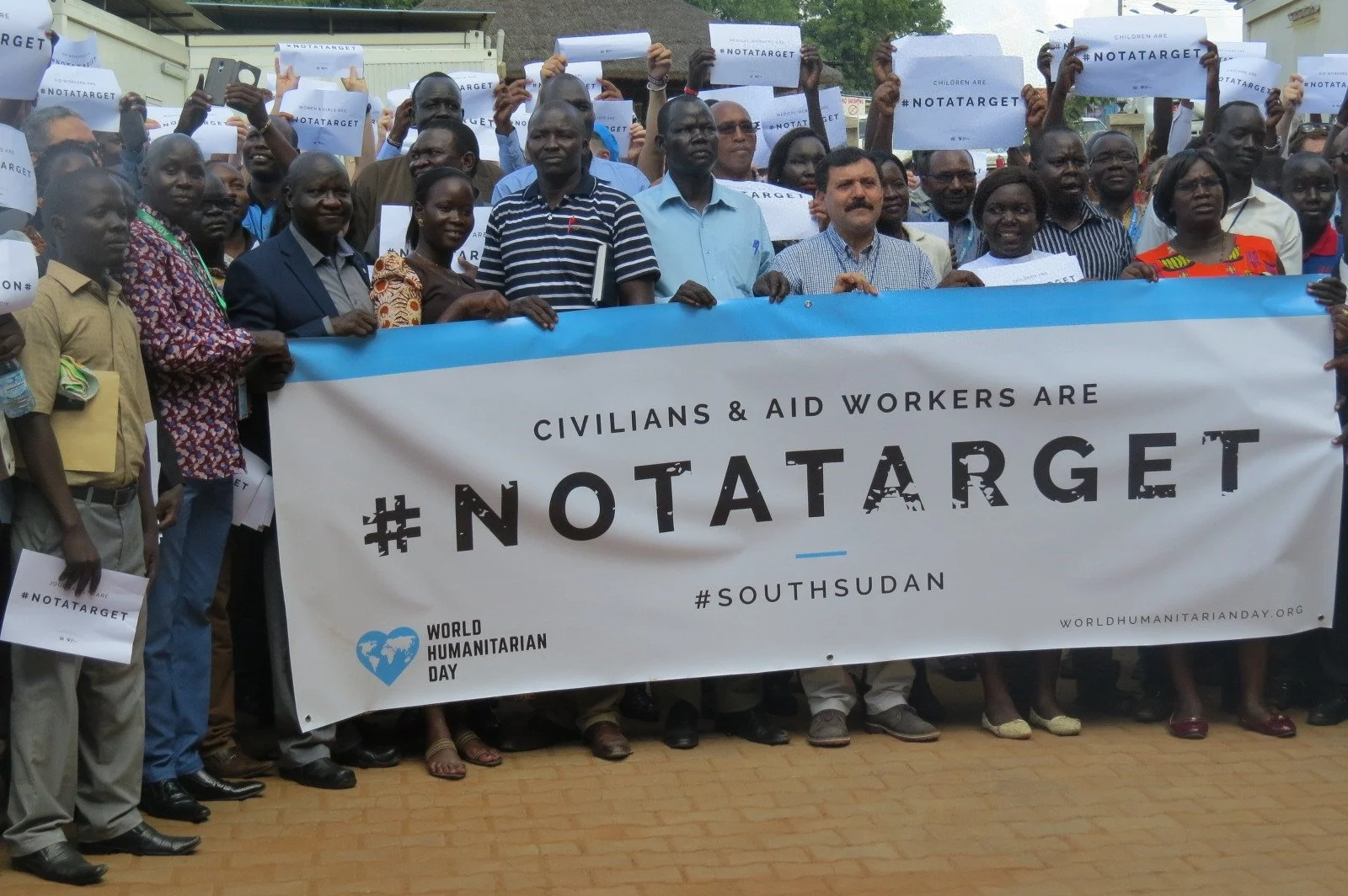

(Denis Elamu/Xinhua)

It was March when Maryam Petronin returned to Mali, only five months after a French hostage exchange guaranteed her freedom from a five-year captivity in the hands of a jihadist group. Petronin, the head of a children’s aid organization in Gao, went despite warnings from French authorities and in the face of a Malian arrest warrant, sparking criticism from the French government, including spokesperson Gabriel Attal, who described her actions as “a form of irresponsibility.” But why was Petronin, an aid worker and therefore a non-combatant in the conflict, kidnapped in the first place? And why was her disappearance upon her return to Mali considered a near eventuality?

The answer lies in a multitude of factors, all pointing towards the same conclusion: aid work is a dangerous game, but even more so as of late. As the New Humanitarian notes, there has been an “increase in politically-motivated violence towards aid workers since 2006”; 2019 and 2020 alone have seen over 800 aid workers killed or suffering serious harm, a dangerous dynamic that could have worrying implications not just for the workers themselves, but the already struggling populations they serve. Determining what drives these attacks is hardly a simple issue of militant groups and conflict zones — in truth, such danger begins with calculated negligence on the part of aid agencies.

There’s an important distinction between the nearly 450,000 aid workers currently in the field — local aid workers are part of the population they serve, while international aid workers are foreign nationals working in affected areas. Theoretically, both groups should work in concert among the local communities, bearing burdens equally, but the reality is far darker: as of 2018, 71% of aid deaths were local workers, a number that has climbed to 80-90% in the past year. As the World Economic Forum notes, concern over aid worker safety has led not to sweeping security reforms for all workers but rather wariness for international expats only, leading local workers to bear the brunt of the most dangerous work in the conflict-affected zones. Take aid responses to the Syrian civil war as a case study: in an effort to evade militant groups, international healthcare workers established bases in nearby Jordan and Turkey, remaining in relative safety while sending aid over to Syrian local staff to coordinate and distribute, increasing their workload while concentrating external attacks on the local workforce. Such a dynamic is not lost on the local staff, who must carry out the most dangerous tasks while receiving not even half the compensation — a recent study in Southeast Asia and Africa found that aid workers receive about a quarter of the pay of their expat colleagues, a disparity that can go up to a 900% difference. Quoted in Bright Magazine, a periodical about the realities of international development, Congolese aid worker Mina noted, “You know that if anything happens, if there’s war, the organization will evacuate the Western staff and leave you behind.”

These sentiments, along with the isolation, fear, and trauma that living and working in conflict zones inherently foster, serve as yet another factor in aid worker deaths. A report published in the Cambridge Journal of Prehospital and Disaster Medicine notes that “the suspected numbers of death by suicide, diagnosed PTSD, depression, anxiety disorders … are considered endemic.” Such a startling rate of death due to mental illness is especially sobering given a 2018 report that states that only 20% of aid workers consider themselves to have “adequate” mental treatment. Take, for example, the case of Steven Dennis, an aid worker with the Norwegian Refugee Council who was kidnapped by a Kenyan militant group before being released four days later. Dennis sued the NRC, alleging negligence and describing obstacles posed by an inadequate support network in receiving treatment for PTSD and other mental struggles. Unfortunately, he is far from the only one in such a situation; commenting on the case in an interview with the Guardian, Steve McCann, director of a humanitarian aid risk management company, noted that “there are many, many, lower quality organisations operating out there … and sometimes they don’t have security.” Other Guardian interviews with aid workers have revealed severe anxiety, depression, PTSD, and even brain damage from working upwards of eighty hour weeks for months in sub-par conditions. Such circumstances not only create and exacerbate existing mental health conditions, leading to suicide attempts, they also wear down aid workers, weakening physical and mental resistance in dangerous situations.

The mental and physical pressures inherent to modern aid work serve as roadblocks workers must confront internally; externally, both international and domestic aid workers must combat the growing politicization of humanitarian aid, and the ensuing military backlash. As a supposedly neutral, lifesaving force, aid work — and its workers — are excellent grounds for rehabilitating a controversial image, a reality of public perception Defense Secretary Colin Powell was evidently aware of when he described humanitarian efforts in Iraq post-invasion as “[winning] hearts and minds...an important part of our combat team.” The danger of this conflation of political maneuvering and delivery of aid, further underlined by the intertwining of NATO and U.S. security policy and aid work, as well as the delivery of aid by military forces in conflict zones, is perhaps best summed up in an interview with a former officer of al-Shabab, a Somali jihadist group, who described the motivation behind his attacks on aid workers as preventing them from “spying, measuring the land and reconnaissance.” In turn, while the Peace Institute Oslo suggests that there is little connection between NATO forces and aid worker attacks, they recognize the correlation between UN Peacekeepers sent to maintain territorial boundaries and a correlating rise in attacks. Regardless of the military force in question, identifying aid workers as political operatives removes the shield of neutrality that should theoretically protect them and other non-combatants from conflict and reclassifies them as threats to militant groups. As UN Deputy Undersecretary-General Jan Elisson noted in a 2014 Security Council briefing, it also limits the parties aid workers can connect with in order to widen aid distribution, therefore restricting and possibly preventing populations locked in conflict zones from receiving aid. The politicization of aid therefore seriously endangers aid workers while disturbing aid flows, undermining the community work necessary to gain a foothold in the social structure of the affected populations and locking off groups in need from possibly lifesaving aid.

However, politicization by state interests is hardly the only non-aid factor influencing aid distribution; donor influence can significantly alter relief plans and the expectations placed on aid workers. As a funding force behind aid projects, donors have significant weight in determining where and when aid should be distributed, at times to the disadvantage of aid workers. In an op-ed in reflection of the death of a former colleague, a current employee of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Aid notes, “donors want to be seen to be doing something — anything — on the humanitarian side ... things can get hairy.” Aid work used for publicity is already intrinsically problematic, but powerful donors desperate for some sort of ‘‘action’’ may force aid workers into unnecessarily dangerous positions. Steve McCann, the security expert in Steven Dennis’s case, agrees, noting that “[d]onors are a double-edged sword… they can also be demanding in a way that makes people go to the edge.” In such incredibly complicated working conditions, an overbearing boss changes from exasperating to possibly life-threatening, encouraging workers to put their safety second in order to make risky trips across blockades and military encampments.

Of course, even beyond such issues — the rampant mental illness and systemic lack of treatment, the politicization of aid by both politicians and donors placing targets on workers’ backs, the grave inequality between expat and local workers — aid work itself is inherently a dangerous profession, requiring unarmed civilians to provide consistent, life-saving aid that abides by best practices in a constantly fluctuating environment. Despite the best threat mitigation possible, some tragedies — such as the killings of aid workers in East Africa and Yemen, where an al-Shabab officer remarked that such acts were carried out to increase morale, allowing them to “destroy… and feel high” — will remain as long as military actors are willing to create conflict.

However, where the factors leading to aid worker deaths can be lessened, it is the moral duty of aid agencies to ensure such actions are taken. Certain causes of aid worker casualties, such as politicization of aid, cannot be unilaterally ended; states must coordinate with agencies to find a mutually agreeable conclusion that protects workers and affected populations first. Similarly, donor influence is to some extent an inherent part of the politics surrounding fundraising. However, there are certain issues that are specifically under aid agencies’ jurisdictions. Internal policies — for example, mental health failures — offer a significant first step.

In the aftermath of the Dennis Stevens case, which exposed significant flaws in the aid sector’s support network, it is clear that agencies must take greater responsibility in establishing stronger mental care resources. As Emmanuelle Lacroix, a human resources manager with the humanitarian organization coordinator CHS Alliance, recognized in an interview regarding Stevens, aid agencies must “ensure comprehensive duty of care is applied consistently for all staff.” However, in order to best serve aid workers, agencies must first be aware of their needs — and in issues of mental health, stigmatization and fear of job loss prevent many from open communication. Instead, aid agencies must focus on establishing mental sensitivity and awareness on the part of the organization in order to foster an environment in which aid workers are comfortable coming forward with their health issues. The Cambridge Journal of Disaster and Prehospital Medicine suggests a thirteen-point plan that focuses on setting pro-mental health norms and formalizing mental health treatment avenues, a crucial beginning to fundamentally transforming the aid sector’s view of mental health. However, shared experience is just as important in diagnosis, treatment, and recovery; for a model of cultural companionship, Germany’s International Psychosocial Organization stands out, connecting Syrian refugees abroad with their countrymen settled in Germany for mental treatment. Such a network for aid workers would eliminate the detached, impersonal nature of navigating mental health pathways in large organizational structures, as well as provide a source of moral support and personal connection.

Aid policy has other problem areas to address as well: namely, the concerning disparity between local and international workers that, in some ways, seems to harken back to the harmful myth of Western saviorism. The most obvious remedy to such a gap is simply to bridge it — to even salaries and equally distribute dangerous operations. However, such a plan is not without its own critics; a 2017 op-ed in the Guardian argued that such a pay gap was a natural byproduct of the extra incentive needed for international aid workers to work beyond their countries, describing the higher pay as an trade-off for the “unexciting reality of earning a taxable income abroad,” noting that foreign aid workers generally do not have significant housing or paid relocation (benefits, it is important to note, that are not extended to local aid workers either). Aid workers deserve proper compensation regardless of place of origin; the idea that international workers deserve higher pay to cope with the same disadvantages as local aid workers is not only remarkably privileged, it also implies that foreign aid workers are inherently necessary. As Stephanie Kimou, the director of decolonial aid organization Population Works Africa notes, “There is an assumption that what is needed here cannot be found from the people who are here.” Reforming the aid industry to address disparities will not only need equal pay, it will require a restructuring of colonialist, Eurocentric perspectives. This has already been reflected in changes by major non-governmental organizations: Save the Children is currently in the midst of moving its main headquarters from European and North American centers to bases in the countries of operation, a process known as localization. As localization becomes more and more common, as pay gaps are bridged, and as the aid field continues to examine its Eurocentric bias, local and international workers will naturally and gradually share the burden of dangerous missions.

However, even beyond accepting security threats, there are also preventative, albeit controversial, actions aid agencies can take in ensuring worker safety. One of the most prominent theories of preventing aid worker attacks is through cultivating and perpetuating “acceptance,” or a toleration of aid and relief efforts in the area by the local community, and, if applicable, groups on multiple sides of conflict. A 2015 paper from the Governance and Social Development Resource Centre at the University of Birmingham notes three critical factors in creating an atmosphere of acceptance: the characteristics of the aid itself, how much the aid is needed by possible anti-aid groups, and the social links between the beneficiaries and anti-aid groups. As the paper notes, in a traditional sense — that is, one that emphasizes humanitarian neutrality and a lack of engagement with militant groups — aid workers can only control the aid they provide. However, even the aid itself is at least in some components beyond individual aid workers’ choice and more reliant upon donor choice and fundraising. This lack of control leaves aid workers with an inability to concretely engage with local communities and possible militant groups, therefore demarcating them as “unaccepted” by the same affected population intended as beneficiaries.

In order to bridge this gap, aid workers in the field have resorted to unorthodox methods, including direct communication with militant groups in order to operate — in particular, aid workers reported engaging with al-Shabab in order to best provide relief in affected areas, even as their superiors maintained that there was no communication. In establishing such avenues, aid workers and aid agencies are able to further increase “acceptance” in militant communities, and therefore gain a greater level of access to conflict zones. Despite the obvious clash of values in engaging with terrorist groups — although it is important to note that such communications are in no way sympathetic to any militant group — aid agencies have found significant benefits; for example, the spread of polio vaccinations in Afghanistan was greatly quickened by Taliban cooperation with WHO and UNICEF. While the idea may seem both counterintuitive and unsafe, the engagement of aid workers with militant groups may indeed be a crucial component in fostering community “acceptance” — tolerance, that is — and therefore best protecting both the mission at hand and the workers themselves. However, hesitation on the part of aid agencies to formalize such strategies, out of fear of misunderstanding or violating counterterrorism laws, has proved an obstacle. Despite pushback, the acceptance and negotiation pathway opens up new possibilities for aid worker security in addressing the root cause of such attacks; further research and widespread implementation may lead to a significant drop in casualties.

Of course, such wide-ranging systemic reform will take time. But how much? A Security Council meeting held in November 2021 recognized the sheer scope of the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan, with the UN Special Representative noting that nearly 23 million Afghans will experience extreme food insecurity in the upcoming months. Humanitarian aid — and workers to coordinate it — will be utterly crucial in preventing death and famine, and is the utmost priority of the United Nations in responding to the crisis. However, with attacks on aid workers at an all time high and increasing, such aid, crucial as it is in Afghanistan and in many conflict zones across the globe, is in danger. For the consequences of restricted aid, one only needs to return to the 2003 UN headquarters bombing in Baghdad, after which much of the humanitarian mission was pulled out, leaving in its wake “famine conditions.”

Aid is necessary, perhaps now more than ever. But aid workers find themselves struggling against an avalanche of systemic, individual, and cultural components that leave their lives at risk. If governments and aid agencies across the globe continue to refrain from launching systemic reforms of internal human resources processes and external community engagement best practices — if they continue to accept the disappearances of Petronins across the world — aid workers and beneficiaries alike will find themselves with nothing to give or receive.

Title quote attributed to Mohamed Abdi, director of Norwegian Refugee Council operations in Yemen.