Conflict in the Caucasus: How Century’s Old Policy Still Affects the Region Today

Photo by ALAIN JOCARD/AFP via Getty Images

On September 19th, 2023, Azerbaijan launched a swift invasion into the Armenian breakaway Republic of Artsakh, forcing its capitulation the next day. Over one hundred thousand Armenians fled the region in the following days, in what Armenia has claimed to be an effort by the Azerbaijani government to ethnically cleanse the Armenian population in the region. The conflict over the small mountainous region, which had raged for 35 years, ended in just one day.

The contentious territory, known as Nagorno-Karabakh, is located in the Caucasus region in the northern Middle East. The territory is significant due to its predominantly Armenian population that is under de jure Azerbaijani control. Azerbaijan considers the region part of its sovereign territory, which it was granted by the Soviet Union in 1923. On the other hand, the Republic of Artsakh, along with its Armenian allies, consider it to be an independent state under the jurisdiction of its native population.

This conflict has seriously impacted the development of these two nations. Azerbaijan and Armenia have had to prioritize military spending over other aspects of the economy, with both countries, as of 2020, standing as the sixth and eighth highest military spenders respectively relative to their GDP. The two states have been forced to build their diplomatic relationships around the conflict, turning into the pawns of larger world powers. The conflict has had a significant effect on economic development, as well. An Azerbaijani blockade on Armenia severely inhibited its economy, while pipelines transporting Azerbaijani oil had to be designed to circumvent security risks with Armenia.

While it might appear strange that this small mountainous region has had such major effects on Armenia and Azerbaijan, a deeper exploration into the history of the region can be helpful in understanding why this conflict began in the first place, and how it could have been prevented.

(Credit: Council on Foreign Relations)

A Centuries-Long History

To understand the history of this conflict, it is crucial to understand the history of the people whom this conflict involves. Armenians first inhabited the region of the lower Caucasus thousands of years ago, eventually founding the Kingdom of Armenia, which stood as a major power in the Hellenistic era Middle East (which was the period roughly corresponding with the 4th-1st centuries B.C.). They controlled an expansive realm in the highland region north of the fertile region of Mesopotamia, surviving for centuries nestled between the great imperial powers of Rome and Persia.

Armenia was the first Christian country in the world, continuing a long Christian legacy with a unique branch of Christianity that differed from the theological beliefs and liturgical customs present in Western Christianity. The kingdom’s long-lived independence came to an end in 428 C.E., when it was finally annexed by the Sassanian Persian Empire. After centuries under foreign rule, Armenian populations gradually became interspersed with the people of their overlords, leading to ambiguous ethnic boundaries — a phenomenon that would become a major source of the current conflict.

One of these interspersed peoples was the Azeris, a Turkic people of the Southeastern Caucasus and Northwestern Iran whose ancestry comprises a mix of native Caucasian peoples and Turks from Central Asia. The Azeris migrated into the region during the Middle Ages. This population is predominantly Shia Muslim, and they are of close ethnic relations to the people of Türkiye, with Azerbaijani President Heydar Aliyev going as far as to describe the two countries as, “One nation, two states.” The homeland of the Azeri people overlapped in some areas with Armenian populations, which resulted in territorial disputes erupting between these two groups following the end of the First World War.

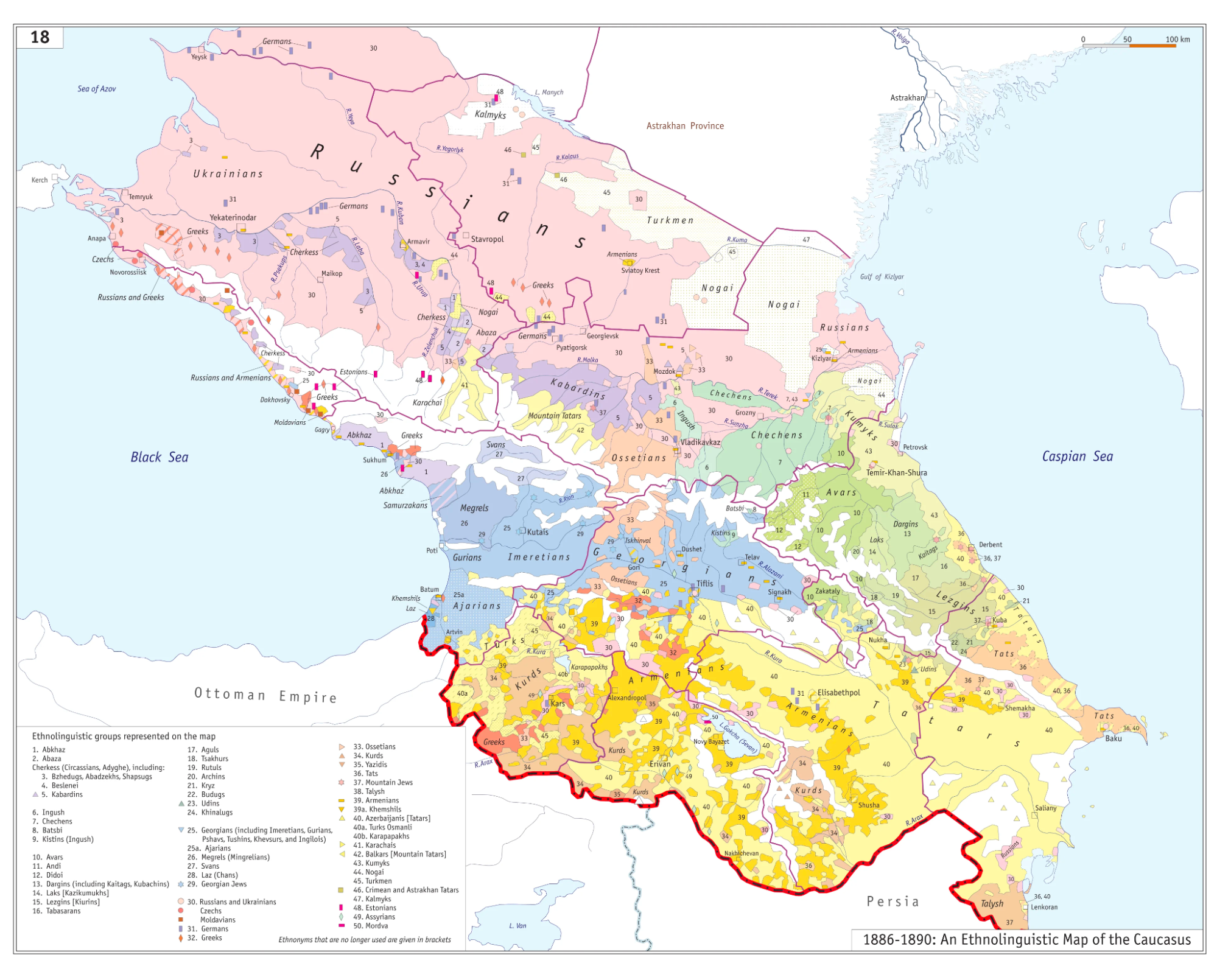

(Credit: A. Tsutsiev, trans. by Nora Seligman Favorov)

Brief Independence

By the middle of the 19th century, both Eastern Armenia and Northern Azerbaijan, the regions that form their respective modern states, wound up under the control of the Russian Empire. However, during World War I, the empire plunged into political disarray, culminating in the Russian Revolution of 1917. This led to the complete collapse of Russian authority in the Caucasus. In the wake of this power vacuum, Armenia and Azerbaijan finally had the opportunity to create their own nation-states after decades of Russian domination.

However, as the two nations began attempting to design their borders on ethnic and historical lines, disputes quickly arose between the nascent republics over the multiple regions containing mixed populations. These conflicts occurred particularly around the mountainous region of Nagorno-Karabakh, which consisted of a predominantly Armenian population surrounded by Azeri populations. Failed attempts to resolve these territorial disputes diplomatically quickly spiraled into war between the two Caucasian republics.

Over the next two years, the situation in the Caucasus grew tenuous. A revitalized Turkish state under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk led a devastating invasion into Armenia from the west, while a new threat emerged to all Caucasian states from the north: the Soviet Union. Following the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, a bloody civil war engulfed the nation. By 1920, the communist Bolsheviks had largely secured their dominance in Russia and began setting their sights on the Caucasus. Capitalizing on instability in the region, the Soviets launched an invasion of Azerbaijan in April of 1920, followed seven months later by an invasion of Armenia, which transformed the two countries into Soviet client states.

The Soviet Dilemma

The Soviet Union, now responsible for managing the territorial disputes between the two republics, chose to handle the conflict in a way that suited their own immediate political interests. Having conquered the two republics at around the same time, the Soviet Union was tasked with finding a resolution that placated each side just enough to prevent major unrest that could threaten Russia’s overall control of the region. In the case of Nagorno-Karabakh, the Soviet Union faced pressure from Azerbaijani officials, who expressed that they would consider any cession of disputed territory to Armenia as “an unexpected change to the old and [would regard the] inability of the Soviet power to secure Azerbaijan within its previous borders as treason, Armeniaphilia – weakness on the part of the Soviet power.” Thus, under this pressure, the Soviet Union thought it necessary to affirm Azerbaijan’s claim over Nagorno-Karabakh, despite its overwhelming Armenian population.

That said, when Armenian nationalists rose up and occupied the mountainous region of Zangezur in southern Armenia, the Soviet Union reconsidered granting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia to appease the rebels. However, they were once again deterred by heavy Azerbaijani pressure. As a compromise, they reassured their promise of Zangezur to Armenia, which had been promised but not delivered to Armenia some months earlier.

Evidently, the Soviet Union did try its best to appease both sides, opting to take the path of least resistance. They did not, however, search for permanent solutions that could have resolved the ethnic conflict in the long term, but rather preferred to find immediate solutions that maintained Russia’s firm grip on the region. In 1923, the USSR made its final proclamation on the region, granting Nagorno-Karabakh — a region with a 95 percent Armenian population — to Azerbaijan as an autonomous region, setting the path for the massive conflict that has engulfed the region since the 1980s.

Only a Matter of Time

Throughout most of Soviet history, the Nagorno-Karabakh problem simmered beneath the surface, rarely serving as an issue for Soviet leadership. However, in 1988, as the Soviet Union entered its waning years, Karabakh Armenians gathered at the center square of Stepanakert — the regional capital of Nagorno-Karabakh — to call for the repatriation of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia proper. These gatherings were quickly followed up by an official proclamation to Moscow by the local Armenian-majority parliament, calling for the transfer of the autonomous region to the Armenian SSR. The initially peaceful demonstrations erupted into violence across Armenia and Azerbaijan in a matter of months, leading to pogroms and gang violence against both populations. After 65 years, the Soviet Union’s doctrine of trying to appease both sides in the short term had backfired horribly.

The conflict spread into neighboring regions. The Armenian nationalism that sparked in Nagorno-Karabakh quickly spread to Armenia proper. As Thomas De Waal, British journalist and writer on the Caucasus, notes, “Armenia, formerly one of the most loyal of republics, turned into the leading rebel in the Soviet Union.” For the first time since 1920, the red, blue, and orange flag from the pre-Soviet republic was flown in Armenia, and the government approved the notion of Nagorno-Karabakh’s integration into Armenia. The Armenian and Azeri minorities in the two republics were purged by the governments and by militants — in often violent manners — and sent back to their respective states. After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Nagorno-Karabakh declared its independence from the newly independent Azerbaijan as the Republic of Artsakh. As a result, war ultimately broke out between Artsakh and their Armenian backers against the Republic of Azerbaijan.

The war lasted three and a half years, claiming thousands of lives on each side. The Armenians proved to be victorious, having secured the majority of Nagorno-Karabakh, as well as its surrounding areas — connecting the enclave with Armenia proper. The war left devastating impacts on both countries. Hundreds of thousands of Azeris were ethnically cleansed from the conquered regions and sent back to sovereign Azerbaijani territory. Reeling from the loss of 20 percent of their land, Azerbaijan slipped into a dictatorship under Heydar Aliyev, whose son still rules the nation today. Meanwhile, an Azerbaijani blockade on Armenia had a crippling effect on its economy.

The Tide Turns

After the ceasefire, things remained relatively quiet, with only infrequent border skirmishes. But this tenuous peace was not to last. The failure of the two nations to make any further political agreements beyond the ceasefire, as well as increasing Azerbaijani militarism, led to war sparking once more in 2020.

This time, however, the situation was different. Azerbaijan boomed economically due to the export of natural oil and grew its military drastically by striking weapons deals with Türkiye and Israel. This edge allowed Azerbaijan to defeat Armenia. Additionally, the subsequent ceasefire allowed Azerbaijan to reconquer a considerable portion of Nagorno-Karabakh, as well as the entirety of the surrounding territory — save for a small region known as the Lachin corridor, which connected Armenia to the enclave and was placed under Russian control.

However, this peace was short-lived. In December of 2022, supposed Azerbaijani environmental activists occupied the Lachin Corridor. Russia, bogged down by its war in Ukraine, neglected to do anything about the situation. By April of 2023, Azerbaijan set up a security checkpoint in the Lachin Corridor and began severely restricting access of goods to the exclaves, creating a siege-like scenario. Finally, on September 9th, 2023, Azerbaijan launched an invasion of Nagorno-Karabakh, conquering it once and for all.

This conquest was followed by the mass exodus of Armenians in the region in the days following. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan had claimed that unless Azerbaijan creates liveable conditions for Armenians in the enclave and develops procedures to prevent against the alleged ongoing ethnic cleansing, mass migration will be seen as the best option for most Armenians, despite Azerbaijani claims that ethnic Armenians will be granted equal citizenship. Now, Armenia hosts the vast majority of Nagorno-Karabakh’s refugees, with the European Commission finding that nearly 200,000 people are in need of humanitarian aid as a result of the conflict with Azerbaijan.

Could This Have Been Avoided?

While, from afar, the dispute over a small mountainous territory may seem insignificant, this conflict serves as a testament to the impact of borderlines on ethnic tensions. In this case, it was the Soviet Union’s negligence in finding a long-term solution to the dispute that allowed the conflict to erupt so violently in the last thirty years. The Soviet Union was concerned with its own pragmatic goal of pacifying the two nations during its takeover and thus disregarded the longevity of the plan. Its ultimate decision led to a situation in which the overwhelmingly Armenian Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast naturally desired a reunification with its mother country, while Azerbaijan, which had held the territory as its own domain for over half a century, understandably desired to maintain its sovereignty over it. What resulted was a 30-year conflict that was almost inevitable after the path began in 1923.

Had the Soviet Union taken a long-term approach, perhaps this conflict could have been avoided. The most obvious possibility would have been the allocation of regions of Armenian and Azeri populations to their respective Soviet Republic, thus preventing areas from existing that consisted of significant ethnic minorities, like Nagorno-Karabakh. While this would have mitigated ethnic tensions, it would have led to a complex border composed of jagged lines and exclaves, likely disrupting the regional economies that developed through natural geography and the infrastructure built by the Russian Empire. Nevertheless, the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan, which is bisected from Azerbaijan proper by Armenia, has existed despite these qualms, suggesting that such a resolution with Nagorno-Karabakh may be feasible.

Another possibility would have been a population exchange. Armenia and Azerbaijan could have split up their border on more sensible geographic or economic lines and exchanged ethnic minorities that had remained within those bounds. Such was the case between Greece and Türkiye, in which Turkish minorities in Greece from the Ottoman period were repatriated with Türkiye, while Greek minorities in Türkiye from the Byzantine era were repatriated with Greece. While Greece and Türkiye do not have amicable relations, they do not suffer from major border disputes and have not been at war with each other for over a century.

That said, the trauma and hardship of abandoning one's home should not be understated. French geographer Raoul Blanchard described the Greek refugees during the population transfer as having been “[g]athered pell-mell on battleships, merchant ships, simple fishing boats and flung hastily on the islands adjacent to the Anatolian coast,” and left “entirely destitute, experienc[ing] the utmost sufferings.” Furthermore, population exchanges come along with almost inevitable humanitarian crises attached, thus outlining a significant limitation of this as a solution for Armenia and Azerbaijan. Nonetheless, a major advantage of this resolution would be the existence of uncomplicated borders rooted in economic lines.

Moreover, regardless of the particular method used, had the Soviet Union pursued a policy of reducing the existence of regions with significant ethnic minorities, they would have prevented the major conflict that has dominated the region these last three decades. History has shown how ethnic territorial disputes can easily scale into major global conflicts. Take Alsace-Lorraine: a region in eastern France with a historical German population, which played a major role in both World War I and II. Similarly in Bosnia and Herzegovina, its mixed demographic of Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) led to territorial disputes which culminated in the Bosnian War of the 1990s and resulted in the genocide of Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats. These conflicts serve as testimonies to the devastating impact ethnic border disputes can wreak on societies.

The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan has claimed the lives of tens of thousands, led to the uprooting of long-lasting ethnic communities, and inhibited the economic growth of each nation. Consequently, it is imperative for world leaders to consider the long-lasting consequences of their actions when addressing ethnic conflicts.