The Path Towards Juvenile Justice Reform

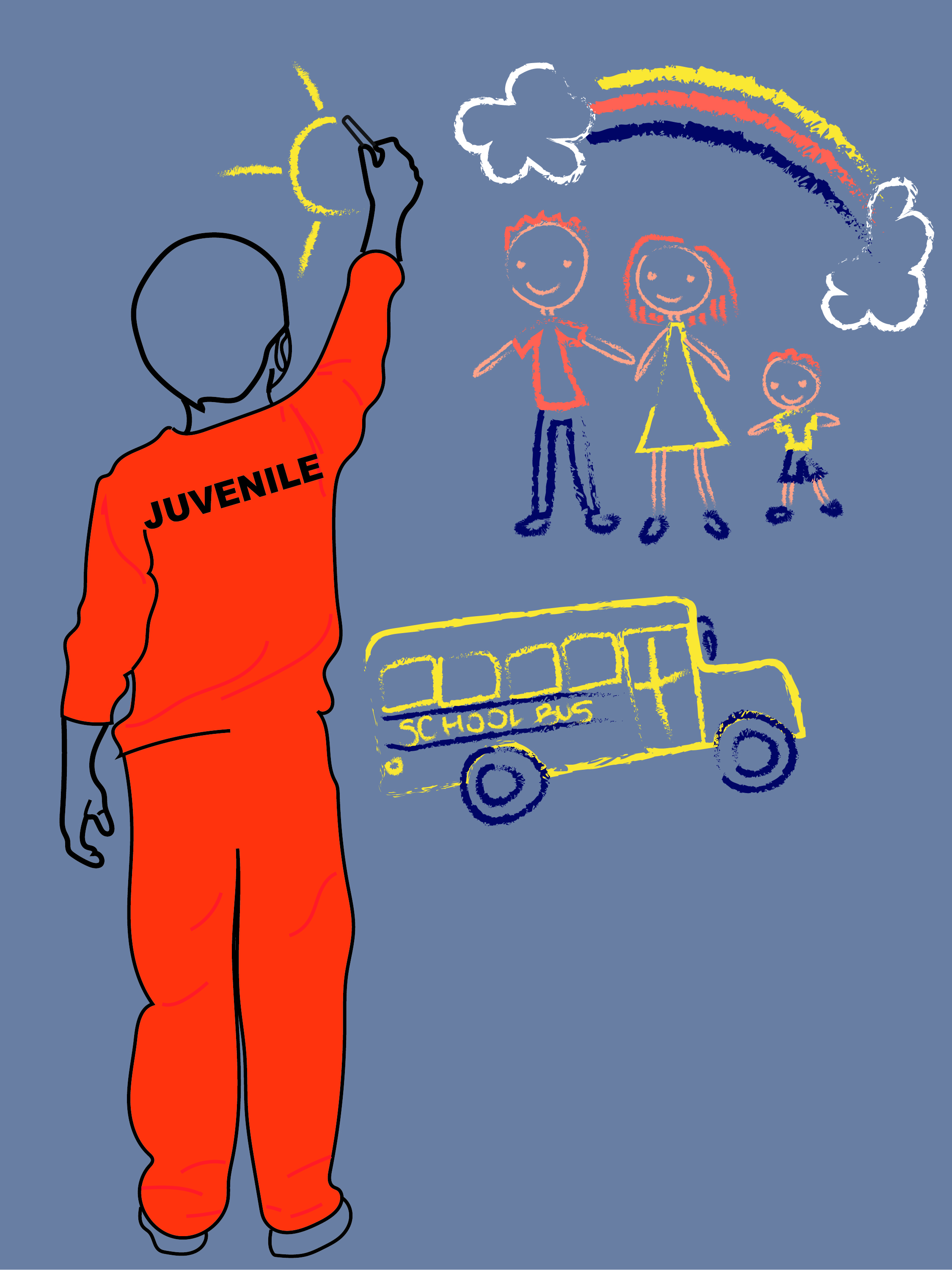

(Jullianne Nubla/Davis Political Review.)

Justice reform in California has been a long-standing issue, prompting years of advocacy for fiscal reform, reduced indiscriminate sentencing laws, stronger rehabilitative programs, and other improvements within the prison system. The economic impact of this creates the necessity to look at this issue in new ways. Most recently, Governor Newsom proposed to improve juvenile justice by shifting the justice department under the authority of a new agency—but will this create an actual impact, or will it simply become a change in letterhead?

After a decade of reform within California’s prison system, Newsom plans to continue reform efforts by placing the Division of Juvenile Justice under the Health and Human Services Agency. Up until now, the division has been under the responsibility of California’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, which also oversees the Division of Adult Institutions. Newsom believes that shifting the Division of Juvenile Justice to the Health and Human Services Agency will boost rehabilitation programs and decrease overall retention rates of imprisoned youths—a prominent issue within youth prisons in the state. He also believes that these programs will decrease the cost of California’s already expensive youth prison system, costing roughly $300,000 per young offender annually—to which he commented is a “ludicrous” cost.

“Juvenile justice should be about helping kids imagine and pursue new lives — not jumpstarting the revolving door of the criminal justice system,” commented Newsom during a press event in Stockton, California. This year’s state budget projected the expected ward population to increase by 97 wards between 2018-19 and 2019-20—for a total of 759 wards. These seemingly small estimates are due in part to State Senate Bill 1391, which prohibits the transfer of minors from juvenile courts to criminal courts. Instead, the state required proper rehabilitative actions prior to any sentencing and became much stricter with who was sentenced to juvenile courts overall. The increase in 2019-20 is also a result of the Young Adult Program—which was authorized in the 2018 Budget Act and raised the age of jurisdiction to 25.

These statistics, although incredibly disappointing, should not be surprising. Currently, the United States has roughly 4 percent of the world’s population, yet holds 22 percent of the world’s prisoners and has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world. California has spent the better part of the last decade fighting to change these statistics. Through years of advocacy, lawsuits, and reform, California’s incarceration rate decreased by 60 percent between 1997 and 2013, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. Even more, in 2013, the state was able to completely eliminate the number of underage youth in adult prisons. Nevertheless, California continues to have one of the highest rates of incarceration in the nation, with 230 juveniles per 100,000 behind bars.

Shifting responsibility of the Department of Juvenile Justice falls under Newsom’s “California for All” State Budget plan. Announced on Jan. 10, under the Public Safety chapter, the plan provides a General Fund of $475.3 million for rehabilitative programs for both adult and juvenile divisions and an additional $2 million to match funds for 40 half-time AmeriCorps members to assist recently released youths. Newsom commented that juvenile justice, whether administered at the local or state level, must help “these kids unpack trauma and [the] adverse experiences many have suffered.” Effectively, he has proposed an additional $100 million for youth trauma and developmental screenings.

Despite Newsom’s hopeful efforts, many are skeptical whether this funding will actually create any kind of impact for these imprisoned youths. “It won’t change the culture or the reality of daily life in those institutions,” said Daniel Macallair, executive director of the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice in San Francisco. He believes that, although Gov. Newsom’s efforts are in good spirit, the California juvenile justice facilities are “plagued by violence” and need more than just increased funding—they need complete restructuring. Macallair proposes an alternate vision of the entire youth prison system, where the state-run juvenile facilities are eliminated and youths are sent closer to home to be put under the supervision of their respective counties.

“Virtually every county in California has surplus space in its county juvenile hall facility right now,” Macallair said. “There’s no need to keep a dysfunctional state system that’s no longer working.” He believes that by placing these troubled youths into county facilities closer to home, they would be able to experience added support from rehabilitation programs within their own communities. Even more, being near their homes would be an added benefit of having the youths closer to their families and, more importantly, adults who can better help them prepare to re-enter society.

George Villa, an activist for juvenile rehabilitation and student at UC Davis, believes that transferring youth to county jails would not only be more cost effective for the state, but it would also improve the overall rehabilitative environment within detention centers as well. Villa is also a member of Beyond the Stats, an on-campus organization that supports the academic success of formerly incarcerated students. For the past three months, he has been working with imprisoned youth to implement El Joven Noble—a ten-week rehabilitative curriculum focused on character development. This program is based on La Cultura Cura, a culturally-rooted healing philosophy that incorporates the use of role models and cultural traditions to cultivate positive and healthy foundations for youth.

Villa believes that programs like these are essential to improving the rehabilitative environment in juvenile detention centers. As a formerly incarcerated youth, Villa described his experiences within the detention center as toxic. “They are a group of grey, identical buildings that don’t encourage normal interactions within the youth,” he said, emphasizing that this is instrumental in the lack of effective rehabilitation within juvenile detention centers.

“Prisons are run by law enforcement,” he continued. “Moving the department of Juvenile Justice under the Health and Human Services Agency will definitely improve the current situation these kids are in.” He is hopeful that having a staff catered to the positive rehabilitation for these youth will greatly impact not only the day-to-day environment within prisons, but their lives after release as well.

Whether Newsom’s proposed fiscal reform will actually bear results or simply continue to fund an already dysfunctional system remains to be seen. After 15 years of continued progress within justice reform, the golden state continues to pursue a “California for All”.