On the Prospect of Abolition

BY SIERRA LEWANDOWSKI

On Jan. 31, the San Francisco District Attorney’s office released a press statement announcing their intention to retroactively apply California’s Proposition 64 to current drug felons. Proposition 64, proposed initially on the November ballot of 2016 and enacted in January of 2018, outlines the legalization of marijuana for recreational use and possession for those over the age of 21. The San Francisco District Attorney (D.A.) has agreed to revisit nearly 4,490 non-violent federal marijuana convictions, dating back to 1975, via a petition process available to felons with the hope of having their sentences reduced to a misdemeanor. Additionally, nearly 3,038 misdemeanors will “automatically be erased” from the record of identified offenders. The city of San Francisco has received great praise and odes of liberal triumph following this announcement last month. San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón remarked, “San Francisco is once again taking the lead to undo the damage that this country’s disastrous, failed drug war” has caused. While this plan to free individuals of their drug-related charges is a positive step towards increasing justice within the state of California, there are still shortcomings and ironies within the policy itself that should be addressed.

It is estimated that there have been over 2,750,000 cannabis-related arrests under California law enforcement between 1915 and 2016. Though addressing nearly 8,000 cases related to marijuana is an important step, the petition process involved burdens the individual by requiring personal time and resources to advocate for their case to be reconsidered. While expunging records for individuals who have been convicted can have positive impacts on increasing their ability to find housing and jobs, the devastating effects of conviction remain. Incarceration’s psychological and emotional trauma cannot be undone. As San Francisco advertises this plan as “an opportunity to rectify wrongdoing,” the state’s ulterior motive is to effectively wipe their hands of the historic effects of the war on drugs and crime by framing their work as a matter of overcoming previously wrong judgments. Marijuana criminalization has demolished communities. While San Francisco gets applauded for its progressivism, individuals remain incarcerated and unable to receive employment or housing for a crime that is increasingly legalized. While recent efforts have begun to to address the impacts of incarceration, these steps cannot be enacted in isolation.

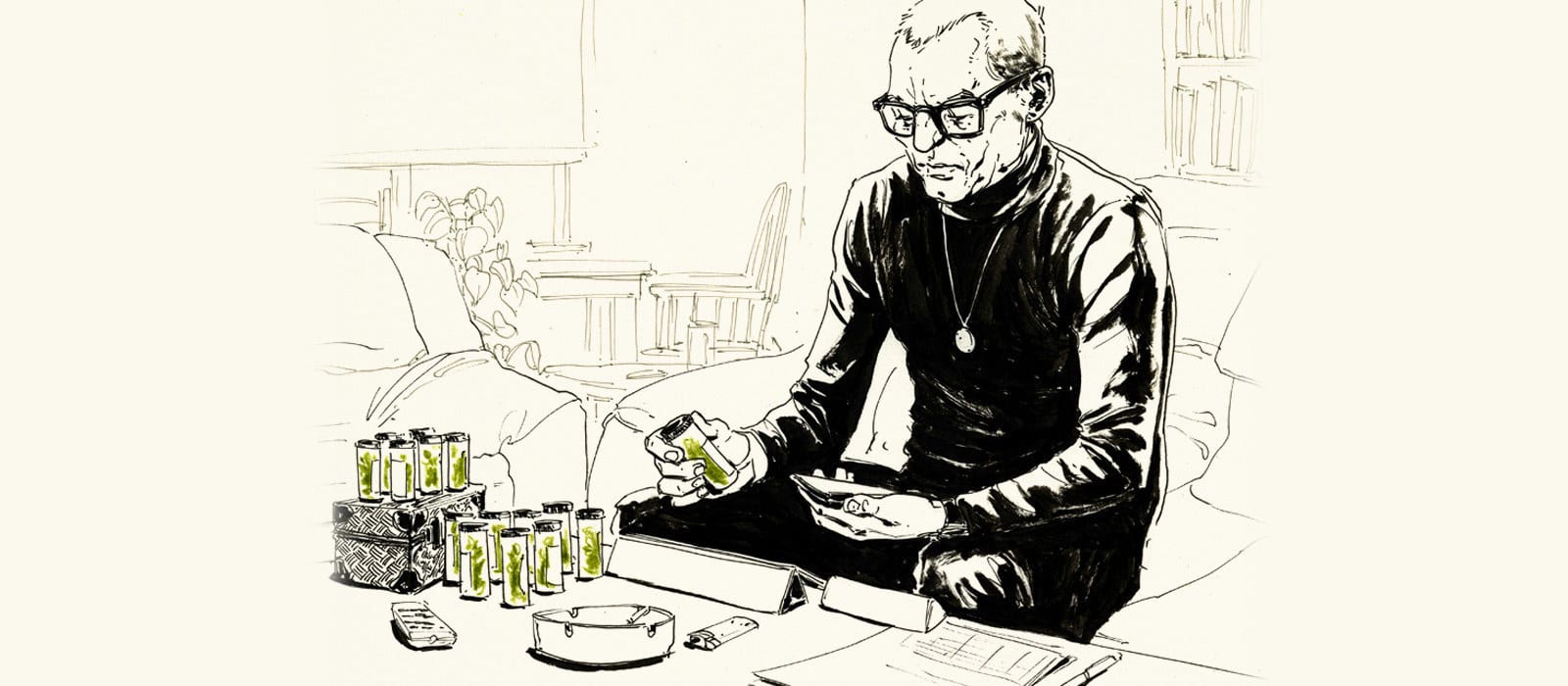

This policy change comes as marijuana is simultaneously becoming legalized across the nation. Currently, eight states and the District of Columbia have recognized the recreational use of cannabis as legal. Whole industries dedicated to its commodification are booming, and it is estimated that 2018 marijuana sales will produce almost $11 billion dollars nationally, with projected increases reaching $21 billion by 2021. As individuals continue to be criminalized and incarcerated, capitalist corporations are profiting. The profit produced by this growing industry not only goes to the state via taxation, but also benefits the disproportionately white and wealth private industries. Despite marijuana use between blacks and whites being “roughly equal,” blacks are 3.73 times more likely to be arrested for its use according to a report published by the American Civil Liberties Union. And of the approximately 3,400 marijuana dispensaries in the United States, roughly one percent are owned by black people. The irony in these policies suggest the bias of criminalization and decriminalization. There is a blatant disconnect between who is afforded the opportunity to have wealth and protection, and which types of people are deemed undeserving of freedom. While whites are able to profit off of the cultivation and use of marijuana, communities of color remain either negatively impacted or left out of its positive benefits. Reporters have referred to this phenomena as the gentrification of marijuana. California, and the nation as a whole, should be focused on eradicating incarceration for non-violent offenders and for petty drug crimes in order to reinvest in broken state infrastructure.

Our societal conception of criminality recognizes acts of crime as a matter of personal moral failing. Individuals become incarcerated because they are identified as bad, have “acted out,” or are deemed harmful to society. Because crime centralizes the individual and requires them to expel their most precious resource - time - as reparation, nothing is done to mitigate the sources of crime in our society. Focusing explicitly on individual acts ignores the greater structures and systems that produce instances of crime. Arresting an individual for illegally selling marijuana destroys the individuals’ life without addressing the societal ills of drug trade, cyclical poverty, and homelessness. From policing to prosecution, the state is able to remain authoritatively objective by simply imparting the rules of the justice system. This perpetuates a cycle of incarceration that continues to lock up bodies without addressing the systems that disproportionately funnel communities of color to a life behind bars. Stemming quite obviously from the legacy of slavery, mass incarceration today has a particularly racialized tone. A lasting history and rhetoric of “tough on crime” policies has worked to successfully shift blame to individuals, while ignoring violence systemic to the state, as incarceration rates remain steadily increasing.

State sanctioned violence and conditions under late-stage capitalism have crafted a society in which individuals are valued based on their ability to contribute to the economy. The historic and institutionalized nature of the U.S. economy as being reserved for the white and wealthy has led to the segregation and disenfranchisement of communities in disinvested areas devoid of access to resource and opportunities. Crime is a systemic product of failing school systems, lagging job growth, limited company investment, inequitable environmental access and high rates of incarceration recidivism that facilitate mass incarceration in communities of color.

Incarceration is a cultural phenomena involving the intentioned and damaging isolation of individuals from their communities, the economy, civic engagement, and access to resources that typically enshrine an individual’s experience of freedom. And yet, the experience of imprisonment is not confined to the jail cell or physical institution, but becomes produced as an internalized characteristic of an individual’s identity. Rather than referring to individuals as people who have committed a crime, we deem them criminals - inseparable from their actions. The stigma of criminalization follows previously incarcerated people and impacts their ability to find housing, get jobs, receive benefits from the state or, in some states, become permanently disenfranchised. While efforts to expunge the records of thousands of San Franciscans is a positive step, true equity and freedom is impossible while the institution of incarceration remains intact. Perhaps the money spent funding the inhumanity of the prison industrial complex would be better allocated to fixing disinvested communities, revitalizing in education, and addressing systemic racism. How can we re-imagine a world without prisons?